I did it! I (somehow) ran – and survived – the Sheffield Half Marathon!

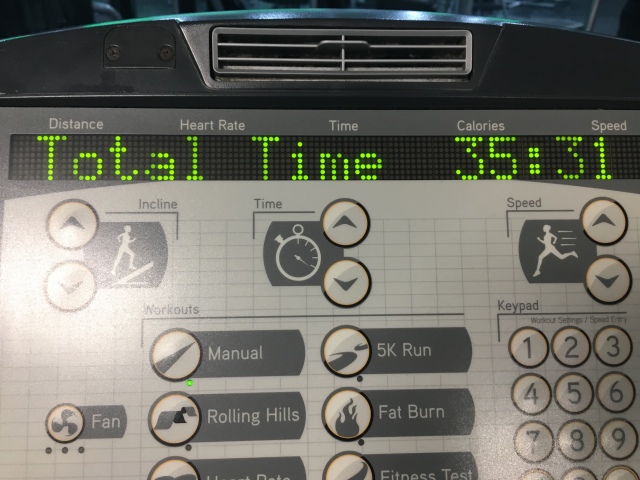

I’m not going to lie, it was brutal. I knew it would be tough, but it was even more difficult than I had imagined. I wasn’t anywhere near as prepared as I’d hoped I would be. In my last post, I wrote about my plans for my first outdoor training run. That didn’t happen. As prepared as I was from a diabetes perspective, I hadn’t checked the weather forecast and woke up to a blanket of snow – so I ended up running eight miles on the treadmill instead.

That meant the 13.1 mile course would be the first time I had attempted running any significant distance outside. It would also be a baptism of fire in tackling Sheffield’s cruelly steep hills. Not ideal.

The night before the race I made sure I had everything I needed to manage my diabetes. I squeezed as many SiS gels as I could fit into my running belt (five), along with a tube of glucotabs, an energy drink, my glucose tester, finger pricker and a handful of testing strips.

This is how it went…

Pre-race blood sugar: 5.7mmol/l

Shortly after meeting a friend and going to collect my race number, I decided to check my blood sugar. This was when I first realised how tricky it as going to be to test during the race. Finding a place to prise my glucose tester from my bulging running belt, take a testing strip out of its packet and prick my finger – among crowds of people – was difficult. I was also worried when I saw the reading. In normal circumstances, I’d be thrilled to see my blood sugar was 5.7 – but, in preparation for a half marathon, I thought it was a bit on the low side. I panic-ate two glucotabs and had an energy gels before I’d even crossed the start line. As the race began, the atmosphere and support were incredible – but for the first two miles I was extremely anxious about having a hypo.

Mile 2 blood sugar: 5.2mmol/l

My initial plan had been to check my blood sugar roughly every three miles, but I was so worried about my lower-than-expected starting point that I decided to stop (rushing to the side of the road and balancing all my things on a wall) to test at mile two. I was really frustrated because it meant I lost the group I had been running with, but I’m glad I erred on the side of caution as my blood glucose had fallen slightly to 5.2. I took another energy gel before embarking on the toughest part of the course. The first five-and-a-half miles of the Sheffield Half Marathon are a relentless uphill slog. My treadmill-only training had not prepared me for the brutality of the course. I have to admit, there were times I was questioning whether I’d be able to make it round at all. Thankfully, I knew my boyfriend would be meeting me at mile five – giving me some motivation to keep going when my body just wanted to stop.

Mile 5 blood sugar: 4.2mmol/l

By the time I got to Andrew I was exhausted and slightly delirious. I checked my blood sugar and it was 4.2 – meaning that, if it continued to fall, I’d have a hypo. I took a couple of glucotabs, which had started to disintegrate after being shaken around in my running belt. I also took another energy gel, despite starting to feel a bit sick. I knew if I could continue for another mile, the rest of the course would be mostly (but not completely) downhill. I was desperately hoping it would become easier.

Mile 9 blood sugar: 9.2mmol/l

Thankfully it did. As the route began its descent back towards the city centre, I actually started to enjoy myself. The Peak District views were absolutely stunning and gave me a much-needed distraction from my increasingly achy legs. I wasn’t running fast, but I seemed to breeze through the next four miles. When I got to the nine mile marker I realised I hadn’t checked my blood sugar for a while, so I stopped at the side of the road to test. I’d lost all dexterity and I fumbled my way through three failed testing strips before I managed to get a reading – 9.2. The run had clearly got my blood pumping because my finger wouldn’t stop bleeding!

Mile 12 blood sugar: 6.6mmol/l

Andrew met me again at the ten mile point, giving me another milestone to focus on. The closer we got to the city, the louder the crowds got – and their cheers definitely helped as I started to struggle again. I knew once I hit mile 12 I was nearly there, but the finish line still felt so far away. I stopped to test my blood sugar again – it had fallen to 6.6. I took another energy gel, gritted my teeth and kept going.

Post-race blood sugar: 7.2mmol/l

I don’t think I’ll ever forget running the final metres towards the finish line. I remember hearing the cheers of strangers calling my name as my weary legs carried me across the line. I had been holding back tears but they spilled over when I saw Andrew.

I can’t really describe how I was feeling. I was relieved, exhausted and in so much pain, but incredibly proud. In part because I’d tackled the distance (my chip time was 2 hours 57 minutes), but mostly because I’d managed to keep my blood sugar under control.

I’d proved to myself I could do it. That I’m stronger than I give myself credit for. And that my diabetes doesn’t have to stop me doing anything.

I’d like to say a huge thank you to all the wonderful people who cheered me on, offered words of advice and helped me raise £480 for the Sheffield Scanner through their generous sponsorship. I was running as part of the University of Sheffield team supporting the £2 million campaign to buy an MRI-PET scanner. I’m so, so grateful for your support!